A quick review of virtually any communication department’s website for prospective students reveals a consistent theme—the university prepares students for a variety of careers. In some cases, university communication programs associate earning a communication degree with hundreds of potential careers. Of course, communication is an interdisciplinary subject fundamental to the human experience, and as such, has broad applicability to education and professional success—as much of the literature demonstrates (Benson, 1985; Bertlsen & Goodboy, 2009; Cohen, 1994; Craig & Carlone, 1998; Curtis, Winsor, & Stephens, 1989; S. P. Morreale, Osborn, & Pearson, 2000; Sherwyn P. Morreale & Pearson, 2008; Weitzel & Gaske, 1984; Wood & Gregg, 1995). Indeed, written, verbal, and interpersonal communication skills regularly top the list of attributes sought by employers in the National Association of Colleges and Employers (2013) annual Job Outlook report. While high-level rationales for the importance of a communication education abound, little research exists connecting the communication education with the qualifications and competencies required for a career as a communication professional (Weitzel & Gaske, 1984). Thus, this study aims to provide communication educators and curriculum planners a minor corrective by providing research on the qualifications and competencies required by employers seeking to hire communication professionals.

Background

To assist a career-minded four-year university in their program evolution from Speech Communication to Communication Studies and their associated curriculum redesign and assessment process, this author researched the literature to understand the jobs marketplace for career professionals, and the qualifications and competencies employers of communications professionals require. Unfortunately, there is little empirical information on the qualifications and competencies required of career communication professionals, nor their implications for curriculum planning. The little research available in the literature is quite dated. Jamieson and Wolvin (1976) conducted a graduate survey of non-teaching positions in the Washington DC area, noting graduates found government jobs in research, analysis, and employee development, Capital Hill positions as press secretaries, office managers, and political affairs consultants, and corporate positions in organizational communication or public relations.

In addition, Clavier, Clevenger Jr., Khair, and Khair (1979) focused their study on higher education employment trends for speech communication academics. While Spicer (1979) identified the principle duties of journalists working in organizational communication and PR, trainers and consultants, and telecommunication experts involved with mass media. Finally, Weitzel and Gaske (1984) identified several careers for speech communication graduates including professor, communication specialist/consultant and training and development, and public information/public relations specialist. Based on Weitzel and Gaskes’ (1984) descriptions, the communication specialist appears akin to the modern organizational communication professional. At the time, Weitzel and Gaske (1984) found the overall quality of career-related research disappointing and argued “much more career opportunity research is needed” (p. 191). Unfortunately, it appears the call for more research went unheeded.

Of course, the job marketplace for communication professionals as changed dramatically since the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, with the arrival of the Internet, World Wide Web, and social media, society is in the midst of a communication technology revolution every bit as significant as the printing press—transforming every aspect of our society, including work. Moreover, the rise of globalization made possible by global communications has equally transformed the workplace, placing a greater premium on communication in the increasingly diverse world of work. Thus, while the centrality of a communication education to developing the communication competencies required of the modern workplace is well-established (Benson, 1985; Koc, et al., 2013; S. P. Morreale, et al., 2000; Sherwyn P. Morreale & Pearson, 2008; Wood & Gregg, 1995), a perspective on current qualifications and competencies required of communication professionals is not. In fact, such a perspective is both timely and critical for educators seeking to prepare students for the demands of their chosen profession. Therefore, this assessment seeks to answer several important questions along these lines:

- Qualifications

- What qualifications are employers looking for in communication professionals?

- What degrees do employers identifying qualified communication professionals look for most often?

- How much experience do employers seek when identifying qualified communication professionals?

- What kind of experience are employers seeking most often?

- Competencies

- What job competencies are employers looking for in communication professionals?

- Skills

- What skills are important for communication students to obtain?

- How consequential are technology skills for communication professionals seeking jobs?

Method

To answer the research questions, this researcher conducted a content analysis of all job posts on a single job aggregation site with communication in the title at a given point in time. The study proceeded in three phases: data collection, coding and analysis, and tabulation of frequency count data for each category and code.

Data Collection

First, all active job posts with communication in the title from the SimplyHired.com job post aggregator were downloaded into text files in their entirety. This author selected SimplyHired.com because it is an aggregator for all jobs and industries in the United States and the advanced search function allows a job searcher to search for keywords or phrases within the job title field and limits the results to only those jobs posted by employers, rather than other job boards. In addition, SimplyHired.com identifies duplicate links by coloring the link differently—a helpful feature to avoid many—but not all—duplicate postings. The search was conducted on April 7th and returned an initial 339 results. Of the original 339 results, 106 were duplicates hidden by the search engine. Furthermore, 56 results were excluded as they described telecommunications engineering jobs with no relation to the discipline. In addition, 20 job posts were excluded because they were duplicates and another 29 were excluded given the job posts were no longer active. Of the original 339 results, 128 active jobs were downloaded into text files for further analysis. These 128 active jobs represent a snapshot, or point-in-time view of many of the active communication job opportunities in the United States.

Coding and Analysis

The second phase of the study was a qualitative analysis of each job post using HyperResearch software to code, define codes, annotate, and ultimately identify themes emerging from the data. This researcher chose to use a deductive approach to the content analysis after iterating through the first several cases, because the category structure became self-evident. Indeed, many job posts display a consistent categorization scheme:

Figure 1

Categorization Scheme

| Categorization Scheme | Qualifications | |||||||

| Experience | Education | Competencies | ||||||

| Amount | Type | Degree | Degree Type | Knowledge | Skills | Abilities | Other Characteristics | |

| Research question | ||||||||

| 1) What qualifications are employers looking for in communication professionals? | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2) What job competencies are employers looking for in communication professionals? | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 3) Given the recent revolution in communication technology, how consequential are technology skills for communication professionals seeking jobs? | X | |||||||

| 4) What technology skills are important for communication students to obtain? | X | |||||||

| 5) What degrees do employers identifying qualified communication professionals look for most often? | X | X | ||||||

| 6) How much experience do employers seek when identifying qualified communication professionals? | X | |||||||

| 7) What kind of experience are employers seeking most often? | X | |||||||

Figure 1. Categorization scheme.

In fact, it is little surprise to find job posts following a largely consistent structure. Indeed, most businesses, government agencies, higher educational institutions, and non-profits run their business using enterprise resource planning software standardizing the “qualifications” structure present in the data. Furthermore, employers seeking qualified communication professionals tend to frame their requirements in terms of qualifications—the qualities that make a candidate eligible or ineligible for a job. Indeed, employers have an interest in using qualifications to weed out inappropriate candidates while yielding a significant number of qualified candidates. Most often, qualifications include education, experience, and competencies. In addition, due to the pervasiveness of job competency analysis in the human resources field, and the use of competencies in human resources selection processes, this author uses the definitions from the HR field as the most appropriate reflection of meaning in the job posts.

Accordingly, “a competency is a measurable capability required to effectively perform work (Marrelli, 1998, p. 10), and are typically involve at least one, or a cluster, of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (Marrelli, 1998). Specifically, Marrelli (1998) furthers defines specific types of competencies:

Knowledge is the information or understanding needed to perform a task successfully…skill is a learned capacity to successfully perform a task or activity with a specified outcome…[and] ability is a demonstrated cognitive or physical capacity to successfully perform a task with a wide range of outcomes. (p. 10)

In addition, in Shippmann, et al.’s (2000) analysis, the authors find the typical competency modeling project results in face valid category labels and descriptor content that “captures the language and spirit that is important to the client organization” (p. 727). Thus, analyzing the manifest content in the job posts makes sense, given the competency model is the lingua franca of employers seeking qualified job candidates and the qualifications and competencies capture what is important to employers in prospective candidates.

Of course, the competency model only addresses the high level categories of a job post, leaving considerable latitude to employers to define the specific qualifications falling within the category structure. Thus, an inductive approach was required to openly code underneath the competency categories into subcategories and codes. Due to the high variability in the jobs available to communication professionals and their associated qualifications, this researcher did not reach saturation until 57 cases were coded. To assure saturation was, in fact, reached, another ten cases were coded for a total of 67 cases.

After completing the initial coding, this researcher went through each code to review the keyword in context, adjusting the coding scheme, refining the operational definition of the code, and validating the specific case’s applicability to the code in the context of the larger themes present in the text. In addition, this researcher revised the coding to assure that the codes were both exhaustive and mutually exclusive. Finally, one category emerged from the data outside of the qualification scheme—job type—a category encompassing whether the focus of the job was on internal or external constituencies. The codebook and operational definitions are detailed in Appendix A.

Frequency Count

After iterating through the cases and codes several times, and finding little more to annotate, adjust, redefine, or recode, this researcher exported the code frequency data from HyperResearch in matrix form. In the matrix structure, the columns including all the codes and the rows included all of the cases, while the intersection held the frequency count of the code within the case. The frequency count data was imported into Microsoft Excel for further analysis including descriptive statistics like count, mean, and standard deviation, as well as the percentage of cases requesting a given qualification at both the code and category levels.

Results

Qualifications

a) What qualifications are employers looking for in communication professionals?

b) What degrees do employers identifying qualified communication professionals look for most often?

c) How much experience do employers seek when identifying qualified communication professionals?

d) What kind of experience are employers seeking most often?

Education

Table 1

Degrees by type requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Required Degree* | % of cases |

| Bachelors Required | 88.1% |

| Masters Preferred/Required | 19.4% |

| Degree not specified | 1.5% |

Table 1. Degrees by type requested by employers by percentage of cases.

*Will not add up to 100% given some cases require a Bachelors and prefer a Masters.

Employers are consistently seeking candidates with at least a four-year—although, caution is warranted in placing too much emphasis on this finding as an indicator of the importance of a degree in the communication discipline. In fact, as outlined in Table 2 below, more than 33% of cases did not identify any specific major, while nearly 38% listed at least three applicable majors. Furthermore, nearly 40% of cases used the phrases related field or similar field. For example, Company A wrote, “A bachelor’s degree is required in journalism, public relations, communications, English or a similar field.”Thus, it appears, the four-year degree requirement helps employers identify a wide range of qualified candidates while weeding out unqualified candidates.

Table 2

Openness to a variety of majors represented by number of majors listed on each case

| Number of Requested Majors Specified | Frequency | Cumulative |

| Eight majors | 0.78% | 1.56% |

| Seven majors | 0.78% | 2.34% |

| Six majors | 0.78% | 2.34% |

| Five majors | 3.13% | 5.47% |

| Four majors | 14.84% | 20.31% |

| Three majors | 17.97% | 38.28% |

| Two majors | 21.09% | 59.38% |

| One major | 7.03% | 66.41% |

| Major not specified | 33.59% | 100.00% |

Table 2. Openness to a variety of majors represented by number of majors listed on each case.

Of course, while employers appear open to candidates in a wide range of degrees, their ideas about which degrees are most applicable to their needs show up in the texts. Specifically, communications, journalism, marketing, and public relations make up the top four requested degrees. In addition, a communication degree is nearly twice as likely to be requested by an employer as any other degree. Interestingly, only one employer—a community college—sought candidates with a degree in speech communication.

Table 3

Degrees requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Most Requested Degree | Percent of Cases |

| Communication | 50.7% |

| Journalism | 28.4% |

| Related or Similar Field | 28.4% |

| Marketing | 26.9% |

| Unspecified | 26.9% |

| Public Relations | 17.9% |

| English | 14.9% |

| Business | 10.4% |

| Graphic or Web Design | 6.0% |

| Public Administration | 3.0% |

| Broadcast Journalism | 1.5% |

| Computer Science | 1.5% |

| MBA | 1.5% |

| Media | 1.5% |

| MIS | 1.5% |

| NonProfit Management | 1.5% |

| Political Science | 1.5% |

| Speech Communication | 1.5% |

| Visual Arts | 1.5% |

Table 3. Degrees requested by employers by percentage of cases.

Experience

Table 4

Years of experience requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Years of Experience Requested | Percentage of Cases |

| < 1 | 0.0% |

| 1-2 | 6.0% |

| 2-3 | 11.9% |

| 3-5 | 10.4% |

| 5-10 | 25.4% |

| > 10 | 10.4% |

| Did not specify | 35.8% |

| Total Cases | 100.0% |

Table 4. Years of experience requested by employers by percentage of cases

Experience matters to employers. While nearly a third of cases did not specify how many years of experience were required, 58.4% of cases required two or more years of experience, while none of the cases sought candidates without experience. This finding is consistent with Zemsky, Shapiro, Iannozzi, Cappelli, & Bailey’s (1998) finding that employers seek experienced employees to avoid expensive in-house training.

Table 5

Type of experience requested by employers by percentage

| Most Requested Type of Experience | Percent of Cases |

| Corporate communication experience | 40.30% |

| Marketing experience | 31.34% |

| PR Experience | 23.88% |

| Advertising Experience | 5.97% |

| Journalism Experience | 5.97% |

| Marketing Automation | 5.97% |

| Social Media experience | 5.97% |

| Broadcast TV Experience | 4.48% |

| College Teaching | 4.48% |

| Corporate Branding experience | 4.48% |

| Graphic Design Experience | 4.48% |

| Leadership Experience | 4.48% |

| Management experience | 4.48% |

| Marketing Measurement | 4.48% |

| Sales Experience | 2.99% |

| Business Experience | 1.49% |

| Content Management Tools | 1.49% |

| Crisis Communication Experience | 1.49% |

| Fundraising and Grant Writing | 1.49% |

| Information Systems | 1.49% |

| Non Profit Experience | 1.49% |

Table 5. Type of experience requested by employers by percentage.

Employers appear to seek candidates with experience closely mirroring the requirements of the job. Consequently, there is wide variability in the types of experience employers are seeking. Of course, when viewing the data, it is important to note that many employers seek a constellation or cluster of experience. For example, Company B sought candidates with “experience in Marketing Communications and branding implementation…experience in media measurement and analysis…[and]…corporate communications experience within a company of global scope”.

Of course, the data still illuminates the type of experience employers most often seek—namely, corporate communication experience, marketing experience, and public relations experience. While there is considerable overlap in what constitutes communication experience in these three disciplines, the experience requirement varies based on whether the job requires a largely organizational, customer/consumer, or media context. As noted in Table 7 below, the jobs vary somewhat in the chosen audience of the communication effort. Roughly 18% of the jobs are internal jobs focused largely on communication with employees, while nearly 27% of the jobs are external jobs focused largely on communication with customers, consumers, citizens, or potential donors. Importantly, more than 28% of jobs focus on both internal and external constituencies requiring candidates with experience in corporate communication, marketing, and/or public relations.

Table 6

Job focus with percentages

| Job Focus | Percent of Cases |

| Internal Communication | 17.9% |

| External Communication | 26.9% |

| Both Internal and External | 28.4% |

| Teaching | 6.0% |

| Indeterminate | 20.9% |

Table 6. Job focus with percentages.

One explanation for the jobs with both an internal and external focus is companies hiring communication professionals increasingly are consolidating the marketing, public relations, and organizational communication functions. In some cases, the companies with a consolidation function are smaller organizations or non-profits. In more than 30% of those companies hiring in an internal and external context, they appear to be consolidating the functions in recognition of the changing nature of communications brought about by the Internet and social media. For example, Company C—a high tech manufacturer—writes:

We’re building a high-performance, global communications team who works at the convergence of public relations, corporate communications, social media and marketing to exceed the demands and expectations of a transforming marketplace. We seek to break beyond the conventional definitions of corporate communications to be one global team who manages the company’s outstanding reputation, delivers impactful outcomes for the business, and tells great stories that resonate in the hearts and minds of our many audiences.

Another example comes from Company D in the financial services sector, writing:

…activities include communications strategy and consulting for internal and external needs; development of a holistic communications plan, including for internal and external audiences; executive presentations, business updates, speaking points, and communication to support major initiatives; and content development for various broader communications such as intranet postings, Ribbit content, and firm-wide emails. Work with business partners to create strategy and develop content for [name redacted] external and internal social media venues.

Indeed, it appears a variety of communication-related functions within the organization are converging in response to a changing marketplace. While it is unclear what specific marketplace changes require a response from these companies; the widespread adoption of social media might be a starting point for further research.

Competencies

Table 7

Percentage of cases with job competency requirements by competency type

| Number of requirements | Knowledge | Skills | Ability | Other Characteristics |

| At least 1 requirement | 37.3% | 97.0% | 65.7% | 50.7% |

| More than 3 requirements | 7.5% | 92.5% | 35.8% | 16.4% |

| More than 5 requirements | 1.5% | 85.1% | 9.0% | 9.0% |

Table 7. Percentage of cases with job competency requirements by competency type.

Cleary, employers place a premium on skills—with more than 85% of cases listing more than 5 skill requirements. According to Paulson (2001), employers are largely skeptical of degrees preferring different measures during the hiring process. Indeed, “buying the necessary skills appeals to some corporations because it is perceived as simpler and more cost-effective than anticipating the rapidly changing workplace and training employees for future skills” (Paulson, 2001, p. 42).

In summary, it appears to this researcher that employers use education to case a wide net on the labor market for qualified communication professionals, while using experience and skills to narrow their search to candidates requiring the least on-the-job or formal training. In addition, while education remains a critical qualification, knowledge appears significantly less important than skills, abilities, and experience in identifying qualified candidates. Furthermore, employers appear to be more interested in skills over other job competencies. Finally, the type of experience employers seek is highly variable and reflects a changing marketplace where traditionally separate functions are becoming more tightly integrating, thus shaping the job competencies employers require.

Competencies

- What job competencies are employers looking for in communication professionals?

Knowledge

Table 8

Type of knowledge requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Most Requested Knowledge | Percent of Cases |

| Industry | 10.5% |

| Microsoft Sharepoint | 7.5% |

| Marketing Communications | 6.0% |

| Crisis Communication | 4.5% |

| Business and Finance | 4.5% |

| Communication Best Practices | 3.0% |

| Communication Knowledge | 3.0% |

| Curriculum and Training Design | 3.0% |

| Media Production | 3.0% |

| Communication Knowledge | 3.0% |

| Communication Strategies | 3.0% |

| Scientific Principles | 3.0% |

| Standards | 3.0% |

| Training Measurement | 3.0% |

| Ethical Communication Practices | 1.5% |

| Lean Principles | 1.5% |

| PR principles and practices | 1.5% |

| Communication Technologies | 1.5% |

| Communication Terminology | 1.5% |

| Facebook Analytics | 1.5% |

| MacOSX | 1.5% |

| News Media | 1.5% |

| Nielson | 1.5% |

| Social and Digital Research | 1.5% |

| Windows | 1.5% |

Table 8. Type of knowledge requested by employers by percentage of cases.

While knowledge was the least requested type of competency, the data provides some useful insights. Whereas employers exhibit wide variability in the types of knowledge requested of potential candidates, there are two types of knowledge that appear important. First, more than 10% seek candidates with knowledge of their industry—a finding coincident with employers need to hire candidates needing minimal training and ramp-up time. In addition, knowledge of Microsoft Sharepoint—a pervasive content management system—is important in 7.5% of cases.

Skills

a) What skills are important for communication students to obtain?

As noted earlier, skills—the learned capacity to successfully perform a task or activity with a specified outcome—appear to be the most important competency to employers. In fact, the texts included so many skills requirements, this researcher further subcategorized the skills category into three subcategories: a) general skills, b) communication skills, and c) technical skills. In addition, for similar reasons, this researcher subcategorized the technical skills category into five subcategories: a) Web and Internet skills excluding social media, b) desktop publishing skills, c) social media skills, d) video, photography, multimedia, and graphic design, and e) digital marketing.

General Skills

General skills are the skills that might be found in any job—not only jobs found in the communication profession, yet are skills relevant to employers hiring communication professionals.

Table 9

General skills requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Most Requested General Skills | Percent of Cases |

| Collaboration/Team Play | 58.21% |

| Organizational Skills | 41.79% |

| Project Management | 37.31% |

| Analysis | 22.39% |

| Problem solving | 17.91% |

| Networking and Relationship Building | 16.42% |

| Leadership Skills | 14.93% |

| Research Skill | 14.93% |

| Critical Thinking | 8.96% |

| General Management | 8.96% |

| People Management | 7.46% |

| Time Management | 4.48% |

| Teaching | 2.99% |

| Negotiation | 1.49% |

| Process Improvement | 1.49% |

| Sentiment Analysis | 1.49% |

| Systems Thinking | 1.49% |

Table 9. General skills requested by employers by percentage of cases.

As the reader will note, collaboration/team play, organizational skills, and project management skills are the most highly sought general skills, followed closely by analysis and problem-solving. This data is interesting for its similarities and differences from the annual NACE Job Outlook Report wherein NACE reports on the most sought attributes employers look for in a candidate’s resume (Koc, et al., 2013). The NACE data is reproduced in Table 10 below:

Table 10

NACE Job Outlook Report 2014: Attributes employers seek on a candidate’s resume

| Attribute | Percent |

| Communication skills-written | 76.6% |

| Leadership | 76.0% |

| Analytical/quantitative skills | 73.1% |

| Strong work ethic | 72.0% |

| Ability to work in a team | 71.4% |

| Problem solving | 70.3% |

| Communication skills-verbal | 68.6% |

| Initiative | 68.6% |

| Detail-oriented | 65.7% |

| Computer skills | 62.9% |

| Technical skills | 61.1% |

| Flexibility/Adaptability | 59.4% |

| Interpersonal skill | 58.3% |

| Organizational ability | 42.9% |

| Strategic planning skills | 33.7% |

| Friendly/outgoing personality | 32.6% |

| Entrepreneurial skills/risk-taker | 23.4% |

| Tactfulness | 22.9% |

| Creativity | 21.7% |

Table 10. NACE Job Outlook Report 2014: Attributes employers seek on a candidate’s resume.Note 1. Adapted from Koc, E. W., Koncz, A. J., Tsang, K. C., & Longenberger, A. (2013). 2014 Job Outlook Job Outlook Survey. Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employers.

Interestingly, the two different sources share a perspective on the importance of working within a team, organizational skills, analysis skills, and problem-solving skills. However, the data from the job posts indicate that communication professionals also need project management skills.

Communication Skills

The communication skills category contains the skills communication professionals might typically obtain through an education in the communication discipline. As the reader might expect, and consistent with the NACE’s annual job outlook report (Koc, et al., 2013), oral and written communication and interpersonal communication skills surface quite regularly in job posts. However, in this researchers reading of the cases, oral and written communication and interpersonal communication rarely were skills differentiating the job from other jobs. Instead, employers seem to view those skills as table-stakes. Indeed, rarely did they warrant more than one line of text:

“Excellent written and verbal communication.”

“Strong interpersonal, written, and verbal communication.”

“Excellent oral and written communication.”

Of more interest to curriculum planners are the communication skills specific to employers seeking communication professionals.

Table 11

Percentage of cases requesting communication skills by skill

| Most Requested Communication Skills | Percent of Cases |

| Oral and written communication | 76.12% |

| Writing | 47.76% |

| Interpersonal Communication | 40.30% |

| Storytelling | 26.87% |

| Communication Strategy and Planning | 17.91% |

| Public Relations Skills | 16.42% |

| Communication Consulting | 14.93% |

| Intercultural Communication | 10.45% |

| Organizational Communication | 10.45% |

| Change Management | 5.97% |

| Persuasion | 5.97% |

| Group Communication | 2.99% |

| Listening | 2.99% |

| Communication Measurement | 1.49% |

| Conflict Management and Resolution | 1.49% |

Table 11. Percentage of cases requesting communication skills by skill.

For example, writing—defined as skill in the process of writing, editing, copyediting, and proofreading—was requested in nearly half of the cases. In addition, storytelling—the skill to identify, write, craft and/or tell stories that resonate with audiences—was requested in more than 25% of the cases. Finally, employers wanted communication professionals skilled in communication strategy and planning, public relations, communication consulting, intercultural communication, and/or organizational communication.

Of further note were the requirements for communication consulting and intercultural communication skills. Frequently, the cases described the need for candidates with skill advising and counseling senior executives on building communication strategies, engaging with the media, crafting compelling messages, and understanding communication options. In addition, the ability to work with and craft culturally-sensitive messages for diverse audiences was highlighted in many cases. For example, one company wrote, “[candidate must] have sensitivity to and appreciation of cultural differences and communicating with culturally diverse audiences.”

Technical Skills

b) How consequential are technology skills for communication professionals seeking jobs?

The importance of technical skills to the communication professional cannot be overstated. In fact, every job post contains reference to at least one technical skill requirement—with the exception of jobs in academia. The range of technical skills required by employers is quite considerable and runs the gamut from the commonplace, like skill using Microsoft Office products, to the niche, like skill using Vocus, a particular marketing automation application. To capture the nuances of the technical skills category, this author created additional subcategories where similar tools with similar purposes existed.

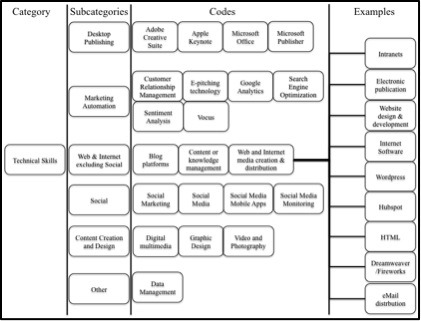

Figure 2. Structure of technical skills coding.

Figure 2. Structure of technical skills coding.

Thus, technical skills were clustered into six additional subcategories:

- Desktop publishing: Skill using personal computing applications to create a wide variety of electronic documents.

- Marketing automation: Skill using marketing software tools, platforms, and approaches to market products and services and raise the visibity of messages and content products for the same purpose.

- Web and Internet excluding social media: Planning, designing, creating, and distributing electronic content or documents via Internet technologies and web platforms including content management systems, corporate intranets, web sites, blogs, and email.

- Social media: Skill using social media applications, platforms, tools, and processes to monitor social channels, engage with constituents, market to constituents, manage brand risk, influence positive brand outcomes, and publish relevant content.

- Multimedia content creation and design: Skill creating, editing, and publishing original multimedia content for electronic or traditional distribution.

- Other: A catch-all subcategory for other relevant technical skills

In general, employers require Web and Internet skills most often. However, social media skills often coincide with Web and Internet Skills. When Web and Internet skills are categorized with Social Media skills, they represent nearly 48% of all requested technology skills.

Table 12

Percentage of Total Technical Skills by Subcategory

| Technical Skill Subcategories | % of Total Technical Skills |

| Web and Internet excluding Social | 31.5% |

| Desktop Publishing | 26.5% |

| Multimedia content creation and design | 20.2% |

| Social Media Skills | 16.4% |

| Marketing automation | 5.0% |

| Other | 0.4% |

Table 12. Percentage of Total Technical Skills by Subcategory.

However, even standing alone, social media skills are more than 16% of all technology skills requested. Of course, reviewing the specific technical skills requested by employers is more illuminating.

Table 13

Technical skills requested by employers by percentage of cases

| SubCategory | Most Requested Technical Skills | Percent of Cases |

| Web and Internet excluding Social | Web and Internet media creation and distribution | 73.13% |

| Desktop Publishing | MS Office | 53.73% |

| Social Media Skills | Social Media | 37.31% |

| Desktop Publishing | Adobe Creative Suite | 29.85% |

| Multimedia content creation and design | 23.88% | |

| Web and Internet excluding Social | Content Management or Knowledge Management | 20.90% |

| Multimedia content creation and design | Digital Multimedia | 19.40% |

| Multimedia content creation and design | Video and Photography | 13.43% |

| Social Media Skills | Social Marketing | 8.96% |

| Multimedia content creation and design | Graphic Design | 8.96% |

| Desktop Publishing | MS Publisher | 5.97% |

| Web and Internet excluding Social | Blog | 5.97% |

| Marketing automation | CRM | 4.48% |

| Marketing automation | Google Analytics | 4.48% |

| Marketing automation | Search Engine Optimization | 4.48% |

| Social Media Skills | Social Media Mobile Apps | 4.48% |

| Social Media Skills | Social Media Monitoring Platforms | 4.48% |

| Other | Data Management | 1.49% |

| Marketing automation | e-pitching technologies | 1.49% |

| Marketing automation | Sentiment Analysis | 1.49% |

| Desktop Publishing | Keynote | 1.49% |

| Desktop Publishing | Technical Writing Editing | 1.49% |

| Web and Internet excluding Social | Video Broadcast and Streaming | 1.49% |

Table 13. Technical skills requested by employers by percentage of cases.

In fact, employers want communication professionals adept at planning, designing, creating, and distributing written material in electronic form over a variety of Internet-based technologies and communication channels. Furthermore, the communication professional needs to be able to use commonplace technologies like the personal computer, Microsoft Office, and email, and also needs to develop highly specialized skills including high-function desktop publishing from Adobe, content management and knowledge management platforms from Microsoft, Oracle, or IBM, multimedia editing software like Final Cut Pro or Photoshop, and enterprise software like marketing automation, social media monitoring, or customer relationship management. Indeed, the communication professional has specialized skills in a world of work dominated by technology. In fact, there were more technical skills requirements than requirements for any other competency including general skills, communication skills, knowledge, abilities, or other characteristics—a telling perspective. Finally, communication professionals need to understand how to choose the right medium to achieve their strategic and tactical purpose given the medium’s unique characteristics, and advise others in the organization along the same lines.

Abilities

Certain abilities—the capacity to successfully perform a task with a wide range of outcomes—are important to employers of communication professionals.

Table 14

Abilities requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Most Requested Abilities | Percent of Cases |

| Multi-task/Work on multiple projects | 43.3% |

| Meet deadlines | 35.8% |

| Prioritization | 31.3% |

| Work Independently | 19.4% |

| AP Style | 13.4% |

| Learn | 4.5% |

| Accept Feedback | 3.0% |

| Balance Workload | 3.0% |

| Deal with Ambiguity | 3.0% |

| Articulate Mission | 1.5% |

| Ask Challenging Questions | 1.5% |

| Brand Creation/Brand Management | 1.5% |

| Design | 1.5% |

| Identify Process Improvements | 1.5% |

| Provide Feedback | 1.5% |

Table 14. Abilities requested by employers by percentage of cases.

In particular, many employers are seeking candidates who can work “in a matrix structure” or “across business units” or “with multiple stakeholders”, thus requiring employees who can work independently on multiple projects simultaneously, manage those projects, prioritize, and still meet deadlines.

Other Characteristics

Other characteristics typically refer to the attributes, attitudes, or behaviors of a person relevant to specific performing work tasks (Marrelli, 1998; Shippmann, et al., 2000). Therefore, the other characteristics of communication professionals are important because they represent employer’s perspectives on the personal characteristics that enable success in the job.

Table 15

Other characteristics requested by employers by percentage of cases

| Most Requested Other Characteristics | Percent of Cases |

| Attention to Detail | 29.9% |

| Self-motivation | 22.4% |

| Creativity | 20.9% |

| Customer Orientation | 9.0% |

| Innovation | 7.5% |

| Positive attitude | 7.5% |

| Technical acumen | 4.5% |

| Work ethic | 4.5% |

| Sense of humor | 3.0% |

| Ethical | 1.5% |

| Results orientation | 1.5% |

Table 15. Other characteristics requested by employers by percentage of cases.

While there is little surprise in the other characteristics data, the emphasis on self-motivation is consistent with the idea that communication professionals frequently need to work on multiple projects simultaneously across a variety of stakeholders—thus, self-motivation is an important attribute. In addition, detail-orientation and creativity are important in general, and specifically for those generating communication strategies, plans, and written content.

In summary, this data on the most requested qualifications and competencies illuminates the most common expectations of employers hiring a communication professional. First, employers expect communication professionals to hold a four-year degree from one of any number of related disciplines. Second, employers expect a minimum of two years of experience and generally prefer more. Third, skills are the most frequently requested competency, with communication professionals expected to be skilled communicators, writers, technologists, collaborators, project managers, and organizers.

Discussion and Implications

The results of this study provide curriculum planners, faculty, and others, the opportunity to reflect on the nature of the communication profession and the relationship between the profession—as described by employers—and an education in the communication discipline. It is not the intention of this researcher to rehash the argument over the degree to which education should prepare students for their chosen vocation. Instead, this research is for those communication departments seeking input from the communication jobs marketplace. In that spirit, the author offers the following discussion and interpretation.

The communication function appears to generally be a support function that works across a variety of organizations, shaping the job competencies employers require. Thus, employers seek qualified candidates that are able to work on multiple projects simultaneously and prioritize among projects effectively, while meeting deadlines. For this reason, employers want skilled collaborators who can work effectively in teams and skilled project managers that can deliver timely results across a matrix-oriented organizational structure.

Furthermore, while some organizations maintain traditional separation between the marketing and organizational communication functions, a significant number of organizations are consolidating communication functions, including marketing communication, public relations, and organizational communication—perhaps in response to cost pressures, the ubiquity of social media, or to realize new synergies between traditionally disparate teams. Nevertheless, the implication for a prospective communication professional is the need to have a broad, multi-disciplinary perspective. Indeed, instead of going down the path of deep specialization, the profession may be moving towards a more broadly capable employee.

Of course, a more broadly capable communication professional needs more than familiarity or acumen with technology, but is skilled in its use. While desktop publishing skills are important, so is the skill to creatively write, edit, proof, and publish compelling stories in a variety of formats and disseminate the assets over a variety of channels based specifically on the purpose at hand. This means that professionals need a level of discernment and skill at selecting and using a variety of technologies to suit their purpose, including email, intranets, content or knowledge management systems, and social media applications and platforms, among others.

Of course, this discussion begs the question: What might curriculum planners and faculty members in the communication discipline do to better prepare their students for work in the communication profession? While each reader should interpret the data and discussion based on their own pedagogical goals, experiences, and inclinations, this author will humbly present several ideas.

First, faculty might consider constructing learning experiences and assignments that closely mimic the situations students may encounter in the workplace. Thus, students should encounter learning experiences that require them to manage multiple projects or tasks for a number of constituents and still meet deadlines. One example of this kind of learning experience is the service-learning or experiential learning project that uses a team-based structure.

Second, faculty should embed technology deep into the curriculum. For example, assignments should require specific electronic outputs across the technical skills spectrum, like building an employee newsletter using InDesign, presenting a group project in Powerpoint, conducting analysis of research data in Excel and SPSS, building surveys in Survey Monkey, building websites using Sharepoint, creating a short video documentary on a particular communication phenomena and editing it with iMovie or Final Cut Pro, or hundreds of other ways.

Third, the department or university should offer workshops or courses on specific technologies that match the demand for skills in the marketplace. Specifically, workshops on tools usage might be the most beneficial. In fact, many technology companies offer deep discounts or provide the tools free for pedagogical purposes in order to build a marketplace of skills. To prepare communication professionals, workshops on using Adobe Creative Suite, Microsoft Office, Apple iWork and iLife, Microsoft Sharepoint, Social media, and Final Cut Pro might be most beneficial.

Finally, faculty of the communications, communication technology, journalism, marketing, and public relations disciplines should work together to develop multi-disciplinary options including new degrees, major/minor structures, concentrations, and other vehicles that allow students to obtain the competencies required of a communication professional.

Limitations

This author conducted this study in a time-bound engagement with the communication department of a higher education institution. Therefore, the researcher did not triangulate the data with hiring managers, candidates, HR personnel, or recruiters. Furthermore, a single coder coded all of the cases. In addition, the researcher did not attempt to identify clusters of job competencies expect when they were readily apparent. Thus, the reader should be skeptical of the generalizability of these findings and interpret the data in light of what they already know about the communication profession.

Future Research

This study fills a long-standing gap in communication jobs research for communication educators. While the discipline has an overwhelming amount of data on the importance and centrality of a communication education to the skills needed for any job in the modern workplace, a critical gap remains. In short, while this study is an important first step, it is only a first step. More research is needed to triangulate these findings with the research of others. In addition, more research is required on how social media and other technologies are changing the nature and character of a job in communications. Moreover, researchers should explore, analyze, and interpret clusters of competencies as they present themselves. Finally, this author recommends an exploration how communication departments are preparing students for the technical aspects of the profession—to both identify gaps and highlight best practices.

Conclusion

Using a content analysis of job posts, this study provides communication educators and curriculum planning personnel insight into the most requested qualifications and competencies required by employers seeking to hire communication professionals. While more research is required to generalize these findings, they remain insightful for those redesigning their curriculums to better prepare communication students for jobs in the discipline.

References

Benson, T. W. (1985). Speech communication in the 20th century. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Bertlsen, D. A., & Goodboy, A. k. (2009). Curriculum planning: Trends in communication studies, workplace competencies, and current programs at 4-year colleges and universities. Communication Education, 58(2), 262-275.

Clavier, D., Clevenger Jr., T., Khair, S. E., & Khair, M. M. (1979). Twelve-year employment trends for speech communication graduates. Communication Education, September, 306-313.

Cohen, H. (1994). The history of speech communication: The emergence of a discipline, 1914-1945. Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Craig, R. T., & Carlone, D. A. (1998). Growth and transformation of communication studies in U.S. higher education: Towards reinterpretation. Communication Education, 47, 67-81.

Curtis, D. B., Winsor, J. L., & Stephens, R. D. (1989). National preferences in business and communication education. Communication Education, 38(January), 6-14.

Jamieson, K. M., & Wolvin, A. D. (1976). Non-teaching careers in communication: Implications for the speech communication curriculum. Communication Education, 25(November), 283-291.

Koc, E. W., Koncz, A. J., Tsang, K. C., & Longenberger, A. (2013). 2014 Job Outlook Job Outlook Survey. Bethlehem, PA: National Association of Colleges and Employers.

Marrelli, A. F. (1998). An introductions to competency analysis and modeling. Performance Improvement, 37(5), 8-17.

Morreale, S. P., Osborn, M. M., & Pearson, J. C. (2000). Why communication is important: A rational for the centrality of the study of communication. Journal for the Association for Communication Administration, 29, 1-25.

Morreale, S. P., & Pearson, J. C. (2008). Why communication education is important: The centrality of the discipline in the 21st century. Communication Education, 57(2), 224-240.

Paulson, K. (2001). Using competencies to connect the workplace and postsecondary education. New Directions for Institutional Research, 110(Summer).

Shippmann, J. S., Ash, R. A., Battista, M., Carr, L., Eyde, L. D., Hesketh, B., . . . Sanchez, J. I. (2000). The practice of competency modeling. Personnel Psychology, 53, 703-740.

Spicer, C. (1979). Identifying the communication specialist: Implications for career education. Communication Education, 28(July), 188-198.

Weitzel, A. R., & Gaske, P. C. (1984). An appraisal of communication career-related research. Communication Education, 33(April), 181-194.

Wood, J. T., & Gregg, R. B. (1995). Toward the 21st century: The future of speech communication. Cresskil, NJ: Hampton Press.

Zemsky, R., Shapiro, D., Iannozzi, M., Cappelli, P., & Bailey, T. (1998). The Transition from Initial Education to Working Life in the United States of America: A Report to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as Part of a Comparative Study of Transitions from Initial Education to Working Life in 14 Member Countries.

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: Literacy at the Interface: A Study of Workplace Literacies for Communication Educators – A Research Proposal | Expressions on Communication - October 15, 2014